In many educational institutes across the country, ragging is seen as a rite of passage, something that all students must take in their stride. It is regarded as a fun, harmless way of settling in, even in premier schools and colleges. For Akshat Srivastava, however, the reality was quite different. “After completing class XII, I joined a dental college,” says Akshat. “At first, the ragging was mild, but soon, many students were forced to perform humiliating acts. Those who stood up to the seniors were badly beaten.”

When Akshat spoke up for a student who was being harassed, he became a target. “I filed a complaint with the college authorities, but they looked the other way. I filed a police complaint, which the college tried to suppress.” Akshat was forced to move out of the hostel. But he refused to back down and the threats continued.

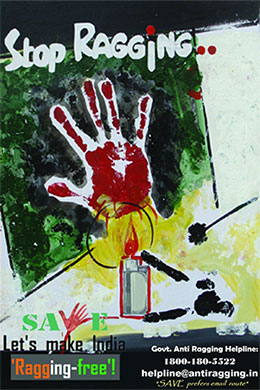

Akshat’s experiences motivated him to join SAVE (Society Against Violence in Education), an anti-ragging NGO launched in 2007 under the name No Ragging Foundation. Its aim is to draw attention to the human rights violations which are taking place in the name of ragging, and to unite isolated protests across the country under one umbrella. Made up largely of young professionals and students, SAVE is against any kind of ragging. Its slogan is ‘Make India Ragging Free’, and it spreads this message through on-campus anti-ragging units, which are made up of students and faculty members.

Advocate Meera Patel, a legal counsellor at SAVE, says that ragging at its core is nothing but about power equations. “The idea is to prove strength, and that is related to masculinity. The idea is to gain respect by force.” Experts point to a strong link between the upbringing of sons and ragging, and believe that it is at the home that sons learn to be bullies. The failure to impart qualities of compassion and respect for others at the home often leads to a violent assertion of strength in the outside world.

Advocate Meera Patel, a legal counsellor at SAVE, says that ragging at its core is nothing but about power equations. “The idea is to prove strength, and that is related to masculinity. The idea is to gain respect by force.” Experts point to a strong link between the upbringing of sons and ragging, and believe that it is at the home that sons learn to be bullies. The failure to impart qualities of compassion and respect for others at the home often leads to a violent assertion of strength in the outside world.

“Bullies inherit or imitate the behaviour of a patriarchal father or relative at home”, says Patel. While such behaviour is usually reported among boys, many girls participate as well to gain acceptance, or be “one of the boys”.

It does not help when college authorities choose to look the other way. “Many teachers regard it as a tradition,” says Patel. “Usually, it is the complainant who has to leave the institution, while the raggers stay on. Most victims are told by their parents to compromise because they have got them admission with much difficulty. The result sometimes is that the boy is dead at the end of the ordeal.”

A common excuse given is that ragging makes one a ‘man’, a stronger person. “The seniors would ask me, “How can you become a doctor without being ragged?” says Akshat. “Those who cannot take it are told they are not manly. The ragging takes an ugly turn sometimes with the victim forced to masturbate.”

“There is a strong emphasis placed on being macho in our society,” adds Gaurav Singhal, National Coordinator, SAVE. “The macho man feels a need to impress his friends, and to show how he has people dancing around him. In most cases, those who have been humiliated through ragging feel they can recover their self-esteem by ragging when they become seniors.” Those who are brought up with different values and are unable to share this mindset, eventually drop out.

“There was one case where the father had given a donation of Rs 20 lakhs to this institution for admission, but his son left midway after he was ragged badly,” adds Mr Singhal. “We have even heard of cases where boys have been raped.”

SAVE reaches out in various ways: helplines and email campaigns, website, media outreach, and seminars. Their website is visited by an average of one lakh students a year, with the highest visitors reported in the four months following July, when fresh admissions take place. They also advise students to call the government’s anti-ragging helpline — 1800-180-5522. If the complainant wishes to remain anonymous, SAVE approaches the college authorities to ensure that action is taken. Through their activities, they hope to eventually build a strong public mandate against ragging, and devise alternative modes of interaction that are humane.

The Supreme Court has taken a strong stand against ragging. In 2007 it passed an order making it obligatory for academic institutions to file FIRs in any instance of ragging to ensure that all of these are formally investigated under the criminal justice system, and not by ad hoc bodies set up by the academic institutions. It also directed all higher educational institutions to include information about ragging incidents in their brochures and admission prospectus.

Following the tragic death of student Aman Kachroo in a ragging incident, in 2009 the University Grants Commission also passed a regulation making it the responsibility of every college to curb the menace of ragging, including taking strict pre-emptive measures, like lodging freshers in a separate hostel, surprise raids and submission of affidavits by all senior students and their parents taking an oath not to indulge in ragging.

Despite these measures, ragging continues to be widely prevalent in some of our best known academic institutions. Many news reports have highlighted the poor response from anti-ragging helplines set up by the UGC and the government. Given that academic institutions are training grounds for India’s future doctors, engineers and administrators, strong pro-active steps need to be taken, starting at the home to ensure that the correct values are imparted to children—both boys and girls.